I think my father’s silence – about nearly everything – was a consequence of trauma. He committed suicide in 1976, just over a month after my wife Kathy and I were married.

My parents were German Jewish Holocaust survivors. They fled Germany after Hitler came to power, but many of my relatives remained and were murdered. My parents told my siblings and me almost nothing about their early lives. Trauma, I think, kept them silent.

So this summer, Kathy and I joined our daughter Sarah and her family for a roots trip to Germany. I uncovered the profound struggles my family endured as Holocaust victims.

I have been seeking German citizenship since Trump was elected in 2016. As a child of two German citizens, I am eligible for citizenship. The Los Angeles German consulate needed my father’s birth certificate, so they contacted the archivist in Gotha. Her name is Julia Beez, and what she found is extraordinary.

The certificate was modified in the 1930s, when my father’s citizenship was revoked because he was a Jew. In the 1950s, they took the trouble to cancel the revocation. These modifications are handwritten on the document itself, so someone took the trouble to find my father’s birth certificate to revoke his citizenship. Then someone else (the handwriting is quite different) took the trouble to find it again and cancel that revocation.

The archivist and I corresponded, and that led to our visit. We were warmly welcomed by Julia, the archivist, by the city’s informal historian, a teacher named Uwe Adam, and by the deputy mayor, Peter Leisner, who presided when I had the honor of signing the “Golden Book” in Gotha’s city hall, and who later hosted us for a banquet.

Gotha is in Thuringia, in former East Germany. The Alternative für Deutschland, or AfD, a neo-Nazi party, had just gained 30% of the vote in the most recent national elections. We talked about that at the banquet, and I think one reason for the warm welcome was to push back against the AfD. Uwe told us the party is most popular among young people.

I am still trying to process our time in Gotha. I learned that my grandfather, Richard, for whom I am named, had five siblings. My father never told me. Richard died at age 56 in 1931, probably of a stroke, but two of his younger brothers were murdered by the Nazis. His youngest brother, Walter, was a teacher. When the Nazis tried to remove him from his school, Walter’s students protested. The archivist and historian told us this was very rare. German non-Jews seldom protested mistreatment of the Jews. Most, I would guess, were afraid. But many, we can also assume, approved of this mistreatment.

The historian, Uwe, gave us a tour of the Jewish cemetery, kept locked against vandals. My grandfather’s tombstone is blank – Hitler youth pried off the metal letters.

Uwe promised he would see to it that the letters would be restored. We saw the tombstones of all my father’s people who died before the Holocaust. Those who didn’t are buried in exile or were incinerated in Auschwitz.

We saw my grandfather’s house and clinic—still quite impressive, right next to the Duke’s summer residence. It is now separated into apartments. His wife’s family owned the even more handsome estate up the street.

I knew Richard’s wife, my grandmother. We called her “Granny Philadelphia” to distinguish her from my other grandmother, “Granny Dolly,” whom we loved. Granny Philadelphia would visit occasionally from Philadelphia, and my siblings and I found her strange. She had a strong German accent which sounded sinister because of the World War II movies we all saw in the 1950s and 60s. She clearly did not know how to interact with American children. My mother did not hide her disdain for her.

Her name was Margarette Simson Ruppel. When my grandfather, her husband, died in 1931, she moved back with her parents, Julius and Clara Simson. In the mid-1930s, she and her parents hid Jews in their house before they escaped, and she herself escaped with her two nieces in 1939.

I know almost nothing else about her. She had a stroke in 1965, and my father found a nursing home for her in Syracuse. My parents had me play my clarinet for her in the nursing home. I was 10, and I didn’t think it was a very nice place.

She died in 1967, when I was 12. The rabbi mispronounced her name at her funeral.

The political is always personal. If not for Hitler and his minions, she might have had a privileged life in Gotha – both her family, the Simsons, and the family she married into, the Ruppels, were quite wealthy. Instead, while she was still in her 40s, she lost everything. She was forced to flee her home and spend the next 30 years in a strange country. She lived with her son, my uncle Jack, who, from what I remember, was a difficult and disappointed person. As I said, I know almost nothing about her, but I can imagine that she was very lonely.

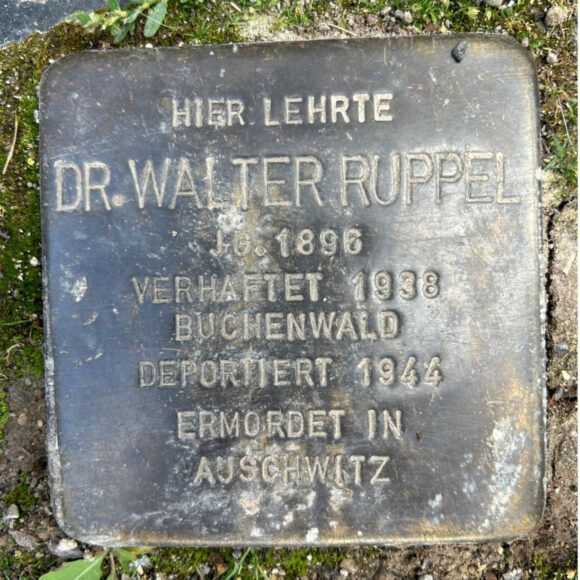

One last thing. The Germans commemorate some of the Jews displaced and/or murdered during the Holocaust with what are called Stolpersteine – Stumbling Stones. Here is the Stolpersteine that commemorates my great uncle Walter Ruppel in the sidewalk outside the school where he taught.

He was arrested in 1938 and sent to Buchenwald. Buchenwald, which means Beech Forest, ironically enough, is in Germany. He was deported in 1944 to Auschwitz in Poland, where he was murdered.

I have asked Uwe to begin the process of creating a Stolpersteine for my grandmother, Margarette Simson Ruppel. He said that he would.