Reaching beyond the rainforest treetops to gather data in space, Chapman scientists stretch the boundaries of collaborative research, creating new landscapes for climate insight.

Climbing into the Canopy

Sometimes scientific breakthroughs start with a slingshot in the wilderness.

Deep in the rainforest of Costa Rica, Chapman University biologist Gregory Goldsmith aims high into the tree canopy and launches the weighted end of a nylon rope that will become his climbing lifeline.

“Basically,” Goldsmith says as a National Geographic video of his research plays on his laptop, “you shoot this line over a big branch and hope that it catches. Then you use mountaineering ascenders and you’re basically pushing yourself up the rope.”

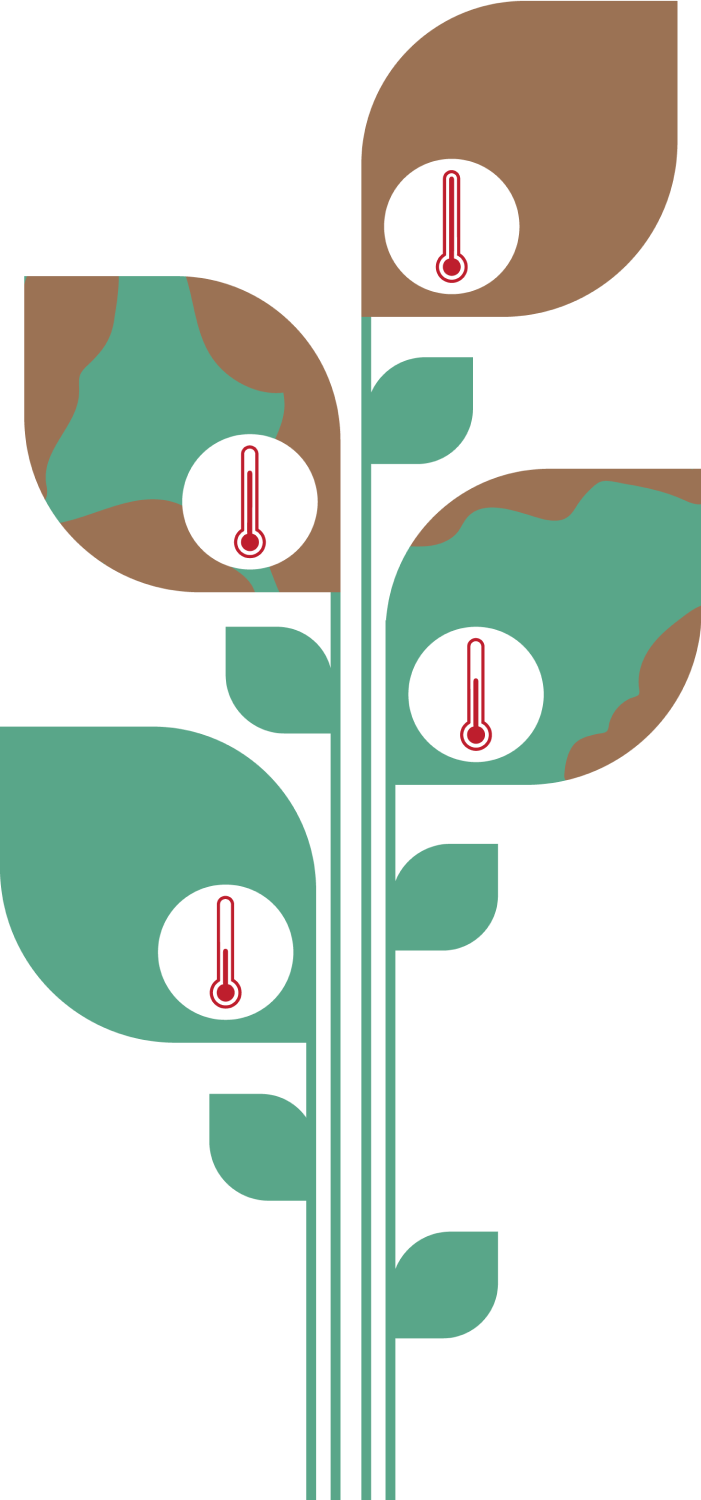

Along for the ride are thermocouple wire and temperature sensors that attach to individual leaves, as well as a car battery to power the capture of information about the health of the trees. As Goldsmith shimmies from branch to branch, applying sensors from leaf to leaf, the data net widens. It’s painstaking and exhausting, but over time Goldsmith gets a read on the forest from the trees.

“If you’re going to understand biodiversity, at some point you have to go to the tropics, and then you’ve got to get into the canopy,” says Goldsmith, associate professor of biology and associate dean for research and development in Chapman’s Schmid College of Science and Technology.

Still, the leaf-by-leaf approach is only one chapter of the story. Getting a next-level grasp on conditions that stretch past the horizon requires a leap into the beyond.

That’s where Joshua Fisher comes in.

— Gregory Goldsmith

DOWNLOADING DATA FROM SPACE

Before Fisher’s office was just down the hall from Goldsmith’s at Chapman, he was a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It was Fisher’s idea to place a thermal infrared radiometer on the International Space Station to study Earth’s ecosystems.

Five years later, that instrument — which is called ECOSTRESS — orbits the globe about every 90 minutes, taking images while capturing temperature and moisture data.

“It allows us to determine plant water use nearly anywhere on Earth at spatial scales that were unthinkable just a few years ago,” says Fisher, associate professor of environmental science and policy at Chapman.

From rainforest treetops to more than 250 miles out into space, a comprehensive portrait of biological stress is now coming into focus.

“The fact that ECOSTRESS can provide 70-meter resolution at 17,000 miles per hour is a game-changer,” Goldsmith says. “Josh’s work gets us to global scale looking down, while I’ve been at leaf scale and finer scaling up. Then we meet in the middle.”

These days, the two share space and ideas on the second floor of Chapman’s Keck Center for Science and Engineering. There, Goldsmith, Fisher and other colleagues translate data into research findings with monumental ramifications.

Chapman professors are analyzing tree leaves and using satellite data to explore the breakdown of tropical rainforests due to climate change.

EDGES OF LEAVES MAY BE THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG

On Aug. 24, discoveries by Goldsmith, Fisher and 16 other scientists were published in a cover story in the prestigious academic journal Nature. Their study, “Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds,” found that rainforest leaves are reaching dangerously high temperatures, triggering alarms about ecosystem breakdown and the dire effects of human-driven climate change.

“We want to understand the future temperatures of tropical forests because they hold most of the world’s species and because tropical forests are important for their climate regulation properties,” lead scientist Christopher Doughty of Northern Arizona University said during a press briefing after release of the study.

“We have known for a long time that when leaves reach a certain temperature, their photosynthetic machinery breaks down,” Goldsmith added during the briefing. “But this study is really the first to establish how close tropical forest canopies may be to reaching these limits.”

The study breaks new ground “because believe it or not, we don’t know terribly much about why trees die,” Goldsmith said. “We know that when a tree is knocked over in a storm and loses its roots, it dies. We know how it dies when there’s a fire. But we know much less about the interactive effects of heat, drought, water and temperature. I think this study really helps us begin to fill in the gap.”

The research also helps illuminate the urgency for action. It includes data about tropical forests from Central America to Australia and Africa to the Caribbean, so the alarms are global, not local. Mass media outlets have taken notice.

“Global warming could push tropical forest leaves past a critical temperature,” one headline reads. “Climate change is already making a small proportion of tropical tree leaves so hot that their photosynthetic machinery bakes and breaks,” Scientific American says in its lead paragraph.

Heightened concern is warranted, Fisher and Goldsmith say. But the Nature article also notes that “it is still within our power to decide … the fate of these critical realms of carbon, water and biodiversity.”

Tropical Rainforests Are Approaching Critical Temperature Thresholds

Leaves in tropical forest canopies already exceed their upper temperature limit about 0.01% of the time.

Increasing temperatures due to global climate change can cause leaves to surpass their upper temperature limit.

Increasing temperatures due to global climate change can cause leaves to surpass their upper temperature limit.

Key Findings

- When enough leaves in the canopy die, the tree dies. A small percentage of leaves are already exceeding these temperatures.

- Tropical forests are projected to withstand a 3.9-degree increase in air temperature before reaching a tipping point.

- The study shows there is still time to prevent the worst effects of climate change on tropical forests.

The study used a suite of observational, experimental and modeling approaches to study tropical canopy temperatures.

NASA Instruments

Tower

Instruments

Leaf Temperature Sensors

Models

Study by Christopher E. Doughty, Jenna Keany, Benjamin C. Wiebe, Camilo Rey-Sanchez, Kelsey R. Carter, Kali B. Middleby, Alexander W. Cheesman, Michael L. Goulden, Humberto R. Da Rocha, Scott D. Miller, Yadvinder Malhi, Sophie Fauset, Emanuel Gloor, Martin Slot, Imma M. Oliveras Menor, Kristine Y. Crous, Gregory R. Goldsmith and Joshua B. Fisher in Nature.

— Joshua Fisher

TRANSLATING RESEARCH INTO POLICY RESPONSE

Since the study was published, Fisher and Goldsmith have been adding extra emphasis to what they see as a historic opportunity for societal response to the threat.

“The media picked up on the gloom and doom, and now we’re trying to reframe the study as: No, this is actually a good thing because we can do something about it,” Fisher says.

Linking their research to actions that protect biological, environmental and policy systems is a key part of the work Goldsmith and Fisher do at Chapman.

In 2022, a predictive model that Fisher helped develop using remote-sensing technology was able to predict every global food security crisis within record at least three months in advance. The research advance, chronicled in the high-profile journal Nature Sustainability, offers the United Nations and other agencies the promise of focusing resources to keep areas of drought and famine from tipping into full-blown crises.

Joshua Fisher (left) and Gregory Goldsmith show students that satellite information can be used to improve environmental issues that impact communities.

Meanwhile, as director of the Grand Challenges Initiative, Goldsmith helps Chapman students turn scientific research and innovation into solutions with direct societal application. He and faculty colleagues mentor undergraduate teams, including four Chapman students who won an award for their 2023 project that uses natural probiotic cleaners to combat superbug infections. Another award-winning Grand Challenges team applied satellite information to improve water management systems.

During the fall semester, Fisher and Goldsmith launched a new cross-disciplinary course that puts real-time ECOSTRESS data in the hands of student researchers. To learn more about that class, see the accompany story, “Chapman Students’ Research Sheds Light on Dangers of Extreme Heat in Orange County.”

“‘Curiosity’ doesn’t intrinsically connect with me the way ‘exploration’ does. For me, as an ecologist, it’s always been about this opportunity to get paid to explore – to discover new things.”

— Gregory Goldsmith

REALIZING THE POTENTIAL OF PROJECT-BASED RESEARCH

In the classroom and the rainforest, the pursuit of innovative ideas continues to drive the Chapman science professors. For Goldsmith, it all connects back to a New England childhood full of outdoor climbing and curiosity.

Actually, he prefers a different term.

“‘Curiosity’ doesn’t intrinsically connect with me the way ‘exploration’ does,” Goldsmith says. “For me, as an ecologist, it’s always been about this opportunity to get paid to explore – to discover new things.”

In ecology, there’s an emphasis on inventing new ways to answer critical questions, he notes.

“Sometimes that means putting something on a rocket, and sometimes that means shooting a slingshot with a rope attached up through the canopy,” Goldsmith says.

It turns out this is the time to tether leaf-by-leaf insights to data downloaded from space.

“One of the reasons Josh and I work so well is that we come at the same question from two different perspectives,” Goldsmith says. “That not only gives us confidence that we got the right answer, but it also gives depth to the information.”

“From a personal perspective,” Fisher adds, “it makes us bigger than we are as individuals.”

It also gives them a spectacular place for their ideas to meet.

“At the top of the trees,” Fisher says.

Story by Dennis Arp

Photography by Adam Hemingway

Design by Cindy Harvard, Julie Kennedy and Vivian To

Rainforest Photo and Video provided by Gregory Goldsmith

Media Contacts

Strategic Marketing and Communications

1 University Drive

Orange, CA 92866

Contact Us

Newsroom Site

Your Header Sidebar area is currently empty. Hurry up and add some widgets.