In the early 2000s, Nike Air Jordans were so coveted by teenage boys that they developed clever tactics to get new versions the moment the shoes went on sale.

Education researcher Quaylan Allen had no idea that the brand’s crazy popularity was also motivating teen entrepreneurs to buy and resell the shoes at a profit. No idea, that is, until he started building his own strategy to capture Black male students’ everyday stories of trial and success.

For close to two decades, Allen has been getting young Black men to open up about their lives, interests and adaptive experiences inside the education system. Applying a sociology research technique called participant photography, he prompts insightful stories that ultimately help teachers and administrators reach students who might otherwise get written off as unreachable.

“The goal is to identify culturally relevant or responsive practices,” says Allen, associate professor in Chapman’s Attallah College of Educational Studies. “The boys and young men I study benefit from the chance to express themselves in different ways, including with photography. It all leads to higher engagement.”

Meet Dontay and Mark (not their real names), two of Allen’s research subjects whose stories came to light thanks to their sharing of photos. One image Mark captured shows seven pairs of athletic shoes on the floor of his closet.

The young men told Allen about their affinity for the Air Jordan brand — Mark from the perspective of a consumer, and Dontay as a seller. During one interview with Allen, Dontay detailed his experience at a local mall when a new line of Air Jordans was released.

“The cops were getting irritated because the crowd kept getting closer and wider, closer and wider,” Dontay relates in a passage that was included in one of Allen’s research papers. “And so at like 5:30 in the morning, they’re like, ‘We’re not opening up the line until you guys get into single file.’ Nobody moved. All of a sudden, VOOSH! The whole crowd just rushes inside the mall — just takes the mall by storm.”

Convincing Participants That Their Voices Matter

Throughout his research career, Allen has conducted hundreds of interviews with working-class and middle-class Black male students as well as with their friends, parents, teachers and others. Included in his research writings are the fruits of his recurring work with 10 Black male students with whom Allen built rapport via participant photos and interviews throughout their high school years and into their college experiences.

His research technique is elemental, but it requires nuance and commitment, Allen says.

“The method is not empowering in and of itself, but finds its power in the negotiation between the moral commitment of the researcher and the agency of the participant,” he explains in a journal article focused on the ethics and benefits of participant photography.

“I had to convince my participants that their voices mattered by demonstrating my knowledge of the problems Black men face, showing deep interest in their well-being and what they had to say, and conveying the social and political implications of not including the Black male voice into the public discourse.”

Allen’s findings fill more than a dozen published papers that now form the basis of a book he is writing for Routledge. The book’s working title is “(In)visible Men on Campus: Black College Men Navigating the Campus Racial Climate at Historically White Universities.”

The title is a play on how Black students tend to be both invisible and hyper-visible in college settings.

“Black men are invisible because they’re typically less than 2% of students on a college campus, which is why overall there’s a lack of support services designed for them,” Allen says. “When I talk with Black students, I hear things like, ‘I need to know where I can get a haircut,’ or, ‘I need access to Black mental health therapists who understand the kind of experiences I’m going through.’”

But then those same students can also become extra visible precisely because there are so few of them, Allen adds.

“They are minoritized, and thus they become targets for microaggressions,” he says. “People assume they are athletes or that they only got where they are because of affirmative action.”

Elevating Black Students’ Stories of Trial and Resilience

Allen’s research draws on his own experiences as a less-than motivated student who ultimately excelled academically and professionally thanks in part to culturally aware mentors. Now he is eager for his research, as well as his recent experience as director of first-generation programs at Chapman, to help others in academic leadership find their way to such mentorship.

Too often in K-12 settings and in higher education, stereotypes infuse practices and curricula while also tamping down both expectations and aspirations, Allen says.

“A lot of research on communities of color tends to be deficit-oriented — here’s what Black students don’t do or can’t do,” he notes. “If you focus on deficits, you’re going to produce deficits.”

Allen champions an asset-based approach grounded in anti-deficit narratives.

“We’re looking at an ecology of factors that might contribute to success,” he says.

“The factors include individual resilience and Black students own agency, but also community factors like support from the immediate family and members of the community as well as social factors like public policy. We look at it all. How do we draw upon experiences of success to articulate new pathways?”

For Allen, participant photography offers a key avenue to insight.

“The method gives students the chance to produce images that reflect things important to them,” Allen explains.

Context comes via interview questions like, “How does this photo relate to your life? What happened before this was shot? What happened after?”

Thanks to Mark’s photo and Dontay’s storytelling, Allen learned about the practice of buying multiple pairs of hugely popular athletic shoes, then sitting on them for a couple of months while the inventory dries up. Ultimately Dontay and his brothers sell the shoes online for more than they paid.

Read more:

Crossing the Border, Building a Bridge

“Clearly, they’re engaging in the free-market system in America,” Allen says. “Teachers can benefit from these stories about everyday experiences and then connect relevant examples of success to what they’re teaching in the classroom.”

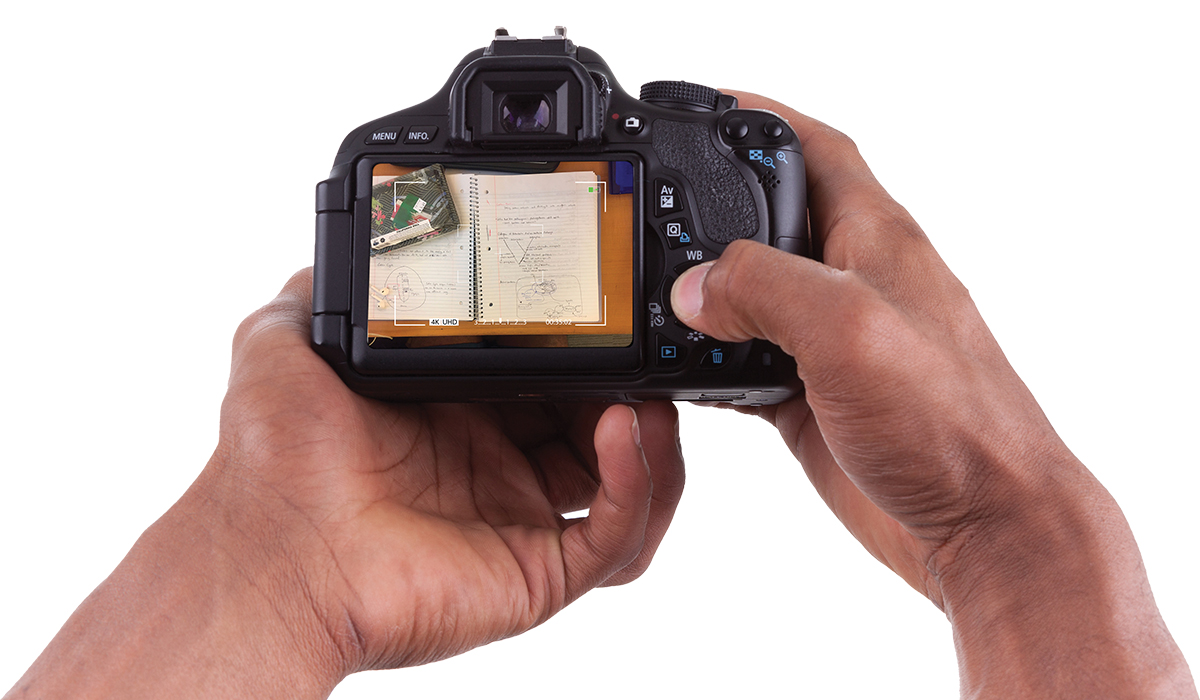

Allen has endured his own trials and errors on the road to refining his research techniques. For his first attempt at participant photography, he gave the students disposable cameras.

— Quaylan Allen

“None of them took pictures because it’s not cool to be seen with a disposable camera,” Allen recalls.

He switched to high-quality digital cameras, and the pictures started sparking stories.

“It speaks to the importance of considering cultural practices and cultural relevance,” Allen says. “We’re working with teenage boys, right? Coolness is a thing.”