There are good reasons to believe that no two tropical forests necessarily have the same canopy temperatures. Similarly, no two trees within a tropical forest necessarily have the same canopy temperatures. In fact, it is not necessarily true that every leaf in a given tree has the same temperature.

For 150 years, scientists have known that when leaves reach a certain temperature, their photosynthetic machinery breaks down, meaning that they can no longer combine light, carbon dioxide and water to make the sugars that sustain them. The question now is: How close are tropical forest canopies to reaching these limits?

For 150 years, scientists have known that when leaves reach a certain temperature, their photosynthetic machinery breaks down, meaning that they can no longer combine light, carbon dioxide and water to make the sugars that sustain them. The question now is: How close are tropical forest canopies to reaching these limits?

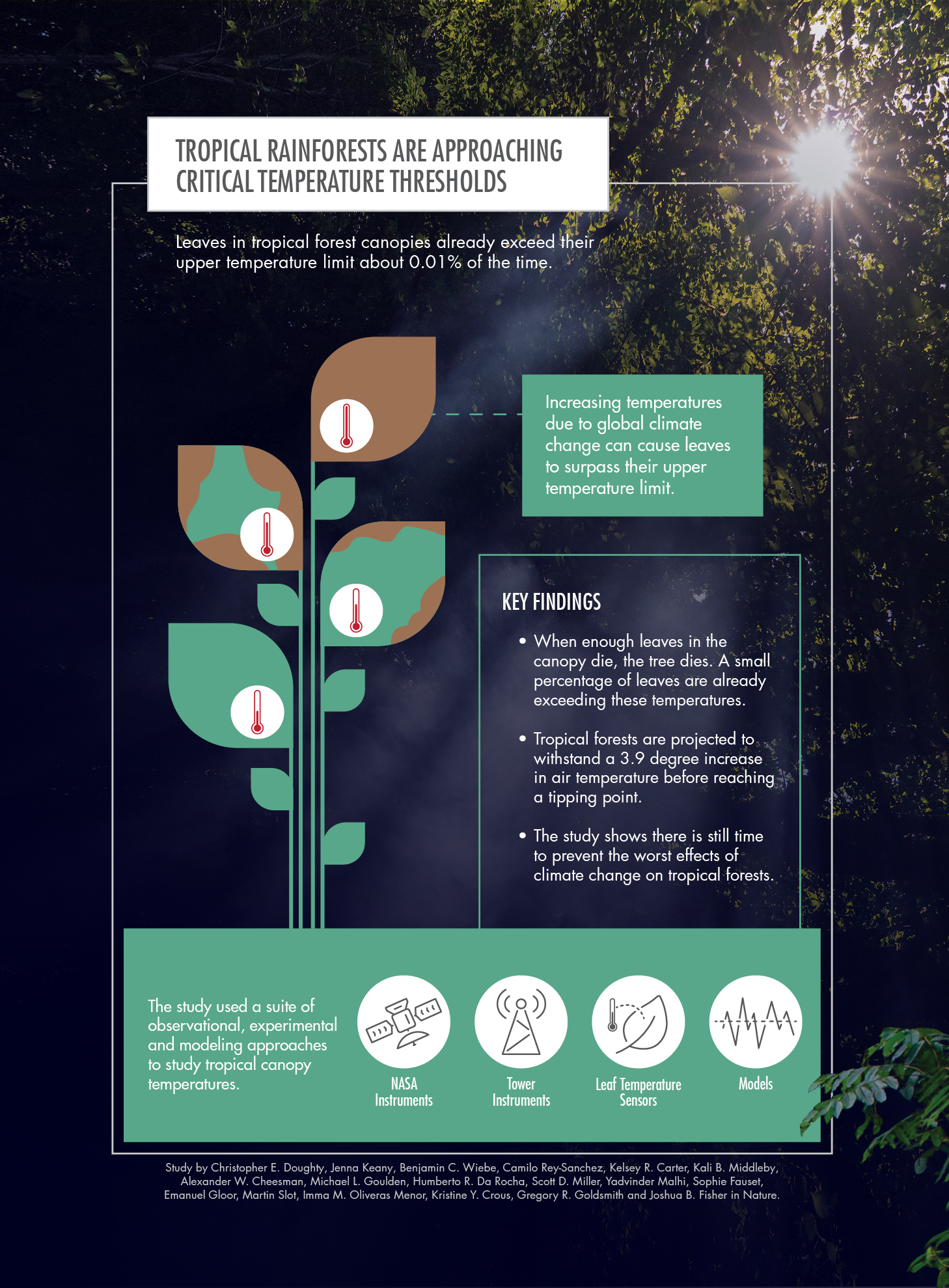

On the heels of the warmest months on record for planet Earth, a new study finds that the world’s tropical forest canopies may be closer to critical high-temperature thresholds than previously thought, but that moderately ambitious climate-change mitigation can avoid these dangerous thresholds.

The study, “Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds,” was published in the prestigious academic peer-reviewed journal Nature on Aug. 24, 2023. The research was funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Department of Education and Training — Australian Research Council (ARC), and Research Councils UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Chapman scientists and colleagues have estimated that the world’s tropical forests can withstand a nearly four-degrees celsius increase in air temperature due to climate change before a potential tipping point in photosynthetic function. A small percentage of tropical leaves are already reaching or exceeding temperatures at which they can no longer function.They studied data from across the world’s tropical forests, including those in the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Africa, Australia and Southeast Asia.

One of the most impressive aspects of the study is the methods used to determine canopy leaf temperatures, which ranged from leaf-warming experiments in the canopy to NASA thermal imaging.

One of the most impressive aspects of the study is the methods used to determine canopy leaf temperatures, which ranged from leaf-warming experiments in the canopy to NASA thermal imaging.

“It is remarkable that we can observe the temperature of the world’s tropical forests from an instrument on the International Space Station orbiting 400 km above Earth’s surface and traveling nearly 29,000 km per hour,” said Gregory Goldsmith, Ph.D., associate professor of biological sciences in Chapman’s Schmid College of Science and Technology. “It is equally remarkable to imagine the painstaking efforts to measure the temperatures of individual leaves in the canopy by hand. We need both the ground- and satellite-based observations to understand the temperatures of tropical forest canopies.”

The Amazon is already experiencing slightly higher temperatures than the Congo basin, and it is at greater risk. “While tropical forests have experienced warming in the past, the current increases in temperature are unprecedented,” Goldsmith said.

If those peak temperatures persist and climate change continues, entire canopies could begin to die. These findings have serious implications because tropical forests are home to most of the world’s biodiversity and are key regulators of our climate.

Goldsmith and Joshua Fisher, Ph.D., associate professor of environmental science and policy and also in the Schmid College of Science and Technology at Chapman University, were among the international team of 18 scientists, which was led by Dr. Christopher Doughty at Northern Arizona University.

“Historically, we have either studied individual trees to gather data at small scales or used satellite instruments to gather data at large scales. What was missing was a way to collect data at small scales across the Tropics,” said Fisher, who helped launch the ECOSTRESS satellite while working as a NASA scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) five years ago before joining Chapman University’s faculty. “That’s where we turn to satellite remote sensing. We were able to measure the temperature of the trees directly at incredibly high resolution, all the way from space, using thermal infrared sensing.”

Yet, “the results do not indicate that reaching a tipping point for tropical forests is fait accompli,” said Goldsmith. “We still hold in our power the ability to conserve these places that are so critically important for carbon sequestration, water and biodiversity.”

Related: Game-Changing Breakthrough for Global Food Security

Related: Game-Changing Breakthrough for Global Food Security