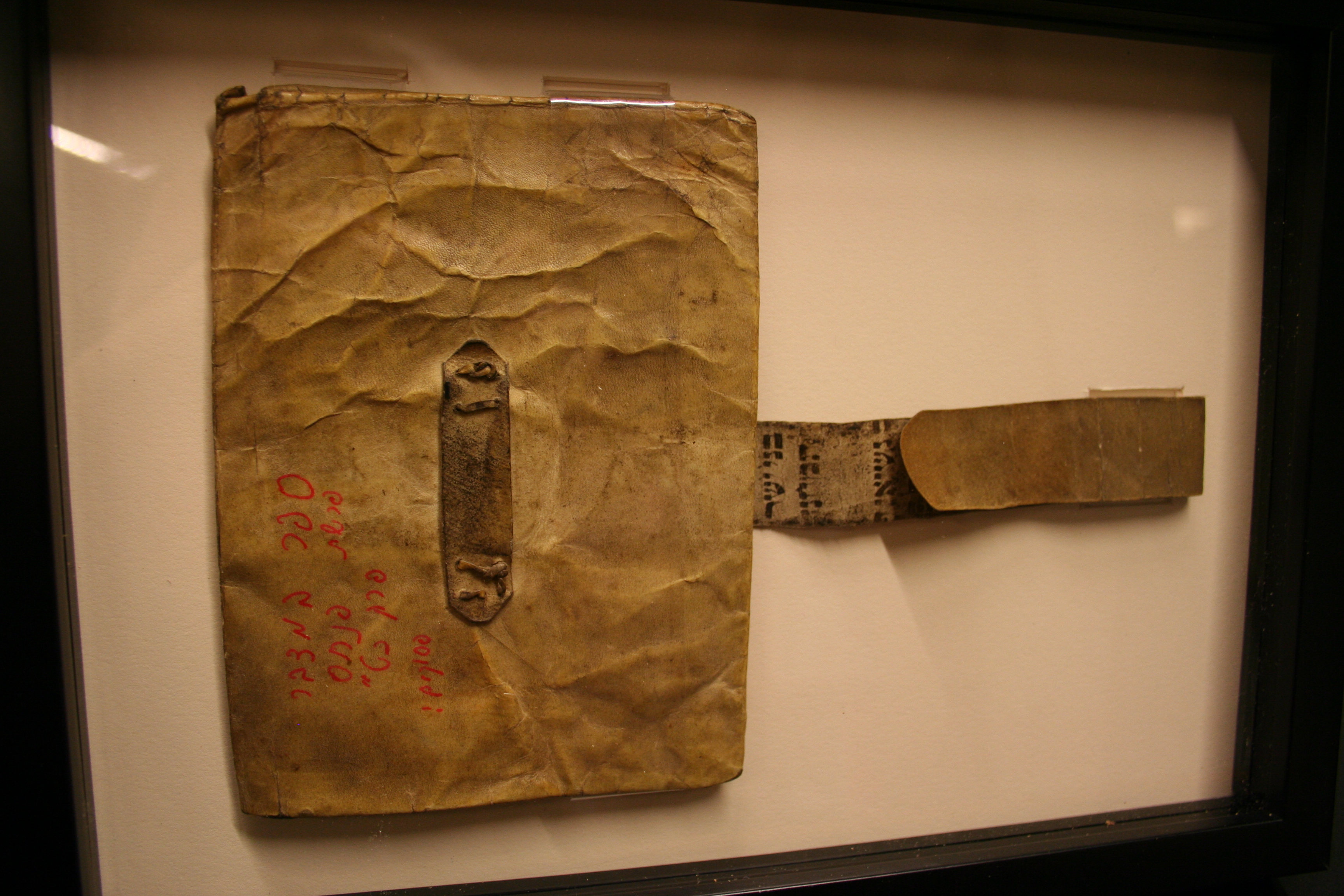

The item in the display case caught Mitchell Raff ’s attention the moment he saw it. The wallet, aged and battered, with Hebrew writing on it, had clearly been made from a Torah. One of the many ways Nazis desecrated the sacred objects they stole from Jews was to turn them into utilitarian things. Though there was no identifying information with the wallet, Raff recognized it immediately.

“This was my father’s,” he said.

Raff was touring Chapman University’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, accompanied by Marcia Rosenberg, a longtime supporter of the Rodgers Center who was eager to share the experience with Raff. Both are children of Holocaust survivors — they call themselves “2Gs,” for second generation — who never suffered the horrors of Nazi concentration camps directly but have lived with the aftermath all the same.

“When you’ve lived as a second generation, there’s a kinship that no one else understands,” says Rosenberg.

Both Raff and Rosenberg knew that their trip to the Rodgers Center would be meaningful, but neither of them expected the trip to be so personally relevant.

A Survivor’s Story

“My father was a survivor,” says Raff, in the kind of careful, matter-of-fact tone some people use when telling emotion-laden stories. “He was in Bergen-Belsen. I think he was also in Dachau, but I know for sure Bergen-Belsen.”

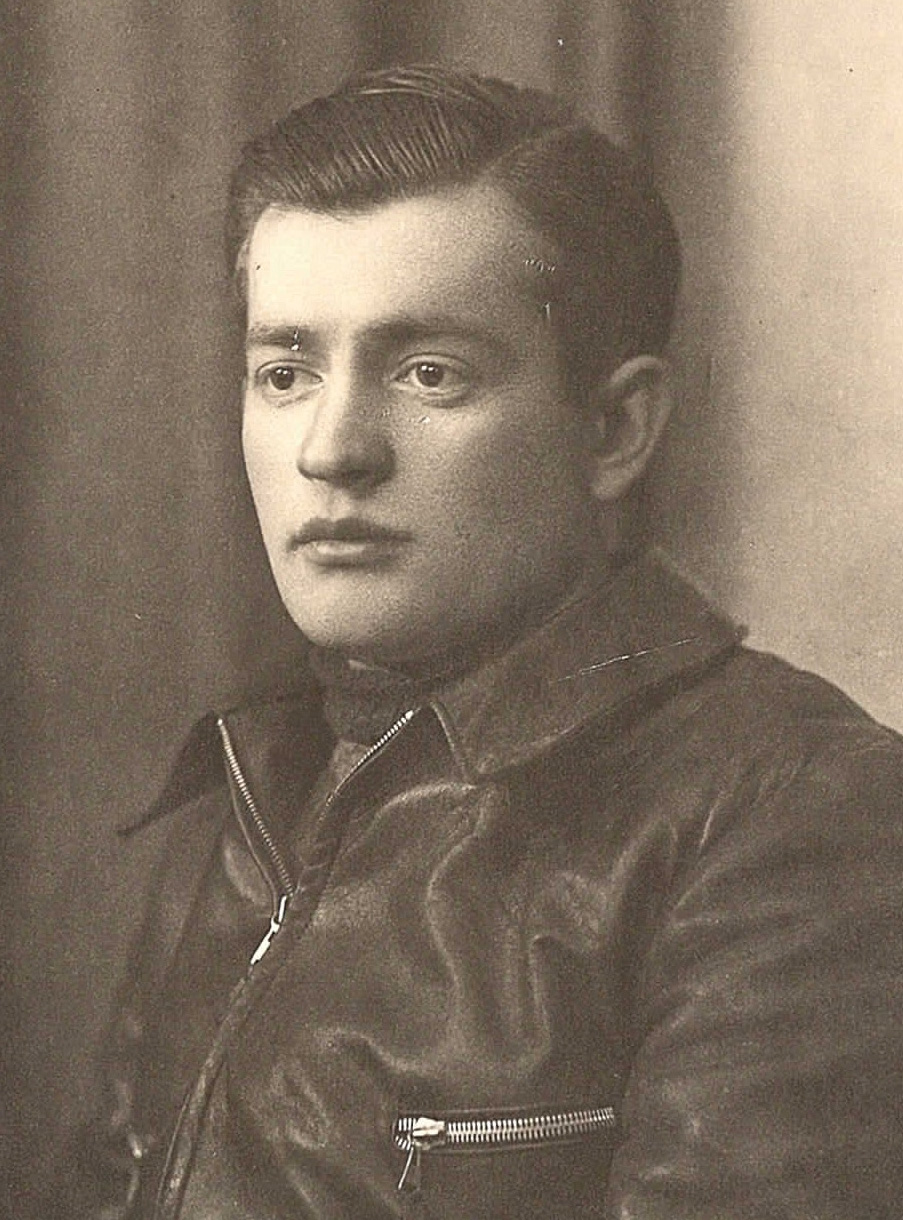

Raff’s father was born Moshe Rafalowicz but took the name Mac Raff when he came to the U.S. after World War II. In 1945, after the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany, he and several other survivors went to the home of someone they knew in town, seeking information about missing friends or relatives.

Mitch Raff knows the story well from his father’s telling. Inside, near the front door, there was a small table, for placing keys and such. On it was a wallet.

“When the man, the owner of the house, left to go to another room to get something or to do something, he sees the wallet,” Raff says of his father. “He recognizes what it is, and my father steals it, basically. And this is how my father, verbatim, told me the story and I’m telling it to you. He says to me that, ‘after we left the house, we walked away.’ He said, ‘I really regret not going back there and killing them. I regret that.’”

The Obligation of History

In the 1990s, Raff’s father gave him the wallet, along with the weighty story of how he came to possess it. But only a few years later he asked for it back, and when Raff’s father passed away, Raff never thought to find out what happened to the wallet. Seeing it in the display case was something of a shock.

After a little detective work, Raff traced the story of the wallet’s journey. His father’s sister, who once lived on the same block as the Holocaust Museum in Los Angeles, had donated the wallet to the museum, which later loaned it to the Rodgers Center.

Once that mystery was solved, Raff was content. He appreciates that the Rodgers Center and Chapman are keeping “the festering, ugly part of history alive, and educating not only their students but also high school students about the Holocaust.”

Though Raff has no previous connection to Chapman, he has arranged a legacy gift to the Rodgers Center.

“My father was a man who was broken from the time he came out of the war,” says Raff. “For him to be able to have this artifact displayed at Chapman with his name on it, ‘donated by Moshe Rafalowicz’ … it is really nice because he was a survivor, and he would have been an unspoken survivor. Nobody would have ever known of him. Now his name gets to live on after his passing.”