Broadway’s popular brand of musical theatre has long regaled its audiences with stories central to the American experience, whether it’s those rumbles between the Sharks and Jets of “West Side Story” or Tevye’s hopeful exodus for America at the end of “Fiddler on the Roof.”

But how do these tales play out when produced in other parts of the world? Are they just restaged wholesale, akin to a subtitled Hollywood blockbuster? Or do discussions about setting, casting and the social and political issues woven into the stories shape the productions to make them more resonant for new audiences?

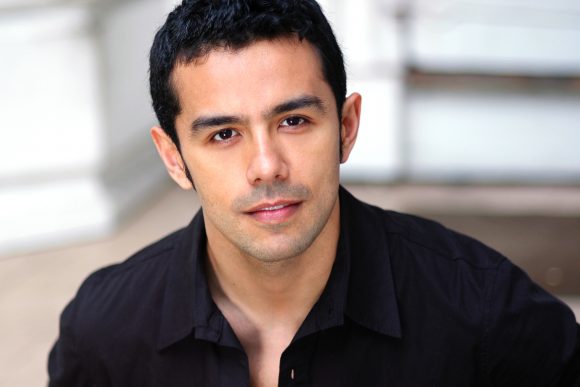

Wilson Mendieta, a professor in the department of dance at Chapman’s College of Performing Arts, asks those questions in a study supported by the university’s Faculty Opportunity Fund.

The idea for the inquiry grew out of Mendieta’s long and successful Broadway career. Throughout those years, the Colombian-American who immigrated to the U.S. at age 11 found his career molded by the realities of being a person of color. And the predictabilities.

“I was able to make a living performing in “West Side Story” (productions),” Mendieta says, referencing the romantic tragedy that reimagines Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” in an ethnically diverse neighborhood of mid-20th-century New York City.

Even still, in those pre-“Hamilton” days he noticed that casting directors stuck to all-white casting for members of the white gang, the Jets, but chose actors from a variety of ethnicities to portray members of the Latino gang, the Sharks.

Upon entering an academic teaching career, Mendieta reflected on those experiences and watched the popularity of American musical theatre rise around the globe, from the United Arab Emirates to Asia. He started thinking more deeply about those topics.

“I noticed they were doing a lot of productions specific to race or ethnicity,” he says, adding that the themes became central to the storytelling.

His research is aimed at discovering how, or if, the themes look and feel different as directors, casting directors and actors navigate these productions.

“If people of color are being represented on stage, how is the presentation of the production taken into consideration? I’m interested in trying to figure out what the conversations were behind those choices,” he says.

He’s also interested in how conventional plot devices of musical theatre connect with other cultures or their folk telling traditions.

“How do the tropes – the ingénues, the romantic leads – translate?” he wonders.

For this project, Mendieta visited South America just before coronavirus travel restrictions kicked in, and found the beginnings of interesting insights – along with some surprises. A rollicking production of “Hello, Dolly” in Argentina was unforgettable, as the audience danced in the aisles and joined in singing the iconic title song of the popular 1964 musical.

Such cultural touches are fun to note, but more critical to him are the decisions behind the productions.

“What’s more important is representation,” he says. “What I’m more interested in learning is whether people are seeing themselves represented on stage.”