Stolen

Justice

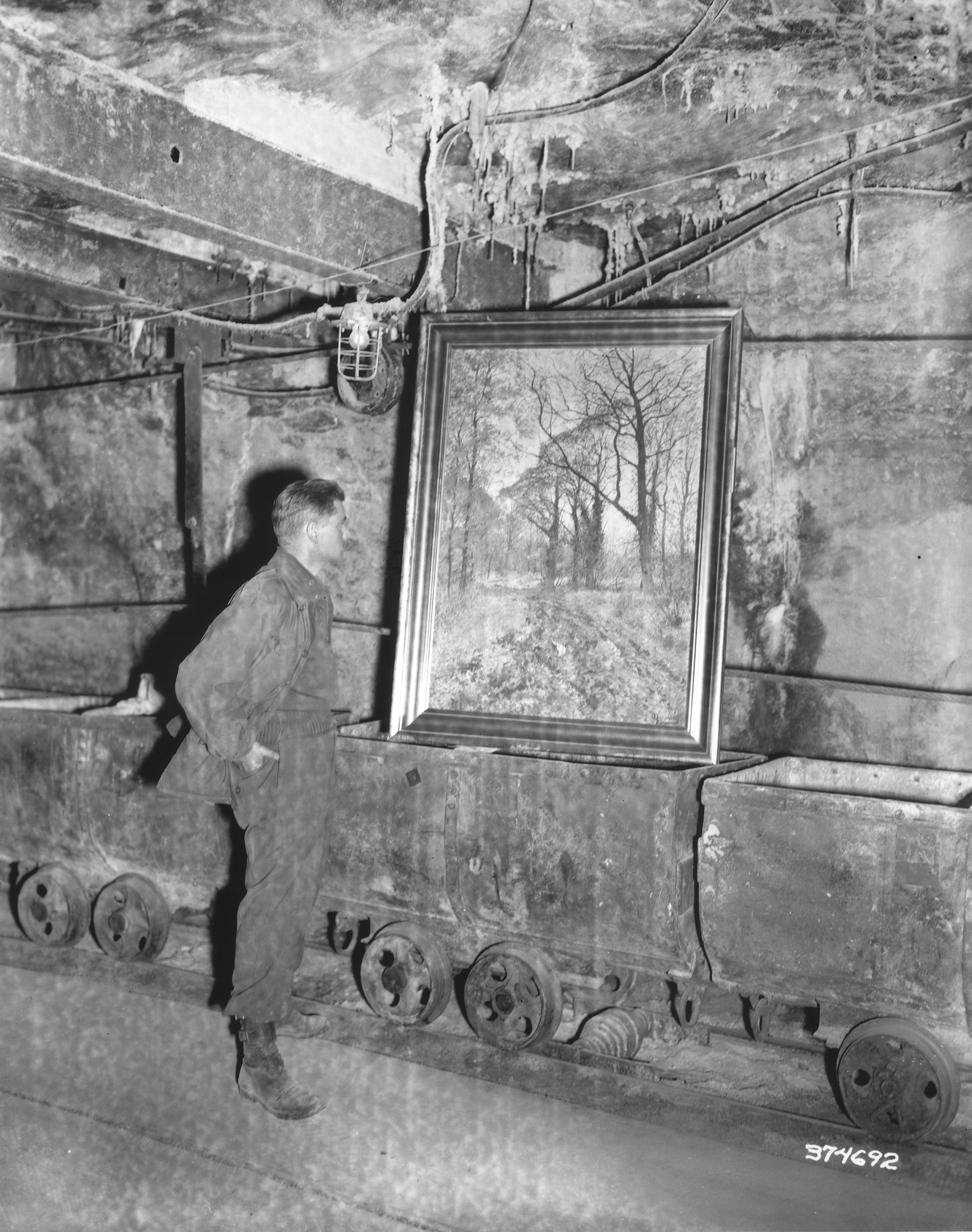

Professor Michael Bazyler inspires young advocates such as Jade Stocks (JD ‘19), left, and Kaylee K. Sauvey (JD ‘18) to seek justice for victims of genocidal regimes. “I think it’s a goal of anyone who pursues higher education to try to make positive change in the world,” Sauvey says.

Twenty years after World War II ended, the shadow of atrocity still shrouded the young life of Michael Bazyler. The son of Polish and Russian Holocaust survivors who as teenagers fled the Nazis to Uzbekistan, Bazyler was 11 when his family immigrated to the United States as political refugees.

For a spirited youngster starting over in a foreign land, the grip of history squeezed a bit too tightly.

The Holocaust was “something I tried to stay away from when I was growing up,” Bazyler says. “It was like the air you breathe. When I saw someone with a tattoo on their arm, it was like everyone had one.”

Over time, however, Bazyler came to embrace his connections to family and community. He found that the more he sought to apply his talents for persuasion, research and scholarship, the more he was drawn to international human rights law. As he saw new examples of genocide and mass theft in places like Rwanda, Syria and Iraq, how could he not take up the challenge of so much unfinished work?

In the 1990’s, Bazyler began researching and writing about the mass theft of Jewish property in Nazi-occupied Europe. He also became vice president of The 1939 Society, an organization of Holocaust survivors, their children and supporters that promotes Holocaust education in partnership with the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education at Chapman.

These days, Bazyler, JD, is a professor at Chapman’s Fowler School of Law who has testified before Congress on Holocaust restitution and has had his work cited by the U.S. Supreme Court. His book “Holocaust, Genocide, and the Law” won the National Jewish Book Award, and his new work, “Searching for Justice After the Holocaust,” chronicles a comprehensive research project he led, examining legislation passed by the 47 endorsing states of the 2009 Terezin Declaration on Holocaust Era Assets and Related Issues. The research project was commissioned by the European Shoah Legacy Institute and was presented in 2018 to the European Union.

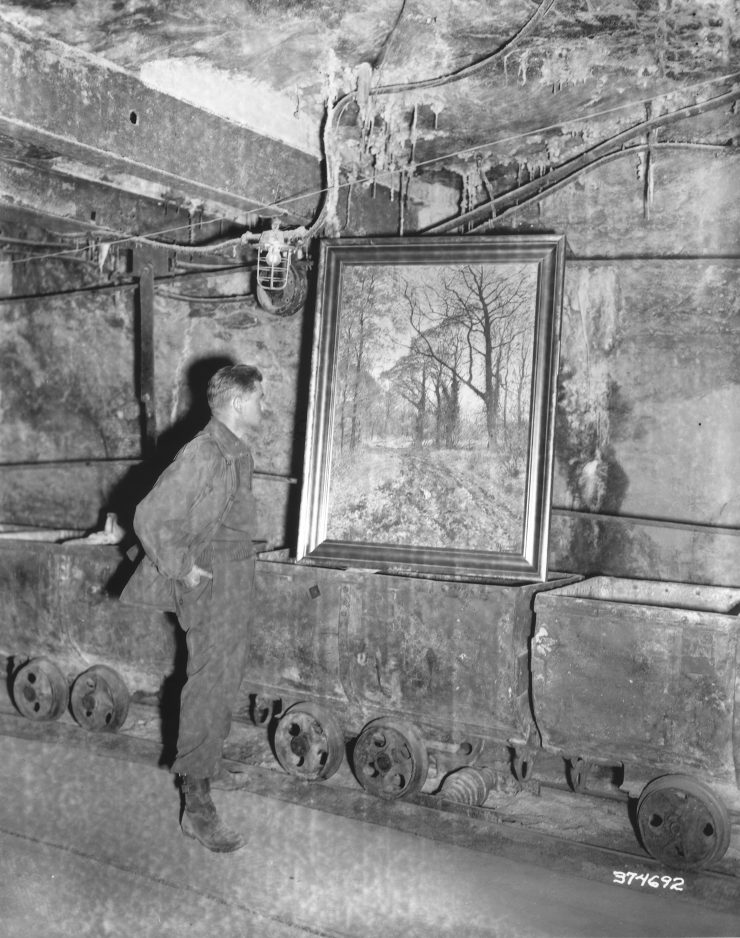

Bazyler’s scholarship reveals that a significant amount of the property stolen during the Holocaust has yet to be returned to its rightful owners, who are seeing the clock tick away on their chances for justice. Estimates are that almost half of the 200,000 remaining Holocaust survivors live in poverty.

“Every genocide is not just about mass killing but mass theft. And the Nazis stole mercilessly from the Jews of Europe.”

Evidence of the need for Bazyler’s research is all around. Recent news reports detail a high-profile case in which a Southern California federal judge allowed a Spanish museum to keep a $30 million Camille Pissarro painting looted by the Nazis, prolonging the 20-year bid for restitution by heirs of the Jewish woman originally victimized by the theft. Bazyler filed an amicus brief in the case.

“Here we are 70 years later, and it’s astounding that these cases are not being resolved,” Bazyler says. “I always preface remarks about restitution by saying that the Holocaust was not about money or property – the Jews were not murdered because they had art. But every genocide is not just about mass killing but mass theft. And the Nazis stole mercilessly from the Jews of Europe.”

Perhaps no one knows better than Bazyler the difficulty of achieving justice in decades-old cases where the trail of property ownership was trampled by regimes exercising untrammeled power. He was co-counsel in the precedent-setting 1990s case “Siderman v. Republic of Argentina,” involving a Jewish businessman who was tortured and had property seized during the “Dirty War” years. The case was mired in the Argentine courts when Bazyler and his legal team had a breakthrough. Because Argentina did business in the U.S., Bazyler proved that the U.S. courts had jurisdiction. Just before the case came to trial, it was settled.

“The U.S. legal system is the main reason the possessors came to take this seriously,” Bazyler says. “The hero of this story is the U.S. legal system.”

The precedent set by the case has helped other genocide victims achieve justice. One case involved an Austrian Jewish emigre living in California who sought return of five Gustav Klimt paintings stolen from her family by the Nazis and subsequently acquired by an Austrian state museum. The case became the basis of the 2015 film “Woman in Gold,” starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. After years of legal wrangling, the woman, Maria Altmann, ultimately won return of the paintings, valued at tens of millions of dollars.

Though such rulings are hard-won and rare, the work continues, encouraging young advocates to fight for justice.

Kaylee K. Sauvey (JD ’18) was in her first year at the Fowler School of Law when she took a class with Bazyler, who then recruited her as a research assistant. Even now as she practices probate, trust and estate law, Sauvey does pro bono restitution work. She combs through lists released by the City of Warsaw, showing Holocaust-era properties eligible for restitution. She posts the information to a database maintained by the World Jewish Restitution Organization.

The Warsaw bureaucracy mechanically follows the letter of Polish law, which says the dispossessed have six months after a posting to file a claim. But city officials actually hope their postings will go unnoticed, Bazyler says

“They want the six months to expire so they can keep the property,” Bazyler laments.

As a Fowler Law student, Sauvey would spend hours in the library, filling binders with restitution-related information for follow-up by Bazyler and others.

“I came to law school fascinated with the subject, and then my professor happened to be this great expert,” Sauvey says. “I think it’s a goal of anyone who pursues higher education to try to make positive change in the world – to seek a measure of justice.”

For Jade Stocks (JD ’19), the catalyst for involvement was a comparative law class taught by Bazyler. She found he was eager to support her research interest in Middle East restitution cases and their connection to foreign policy. Professor and student now share a research interest in a huge Jewish Iraqi archive recovered from Saddam Hussein’s palace during the Iraq War. The archive documents a time when Baghdad had a thriving Jewish population.

“Over the years, almost all were killed or left,” Stocks says. “It’s important research, from a historical, moral and legal point of view. It raises a lot of questions.”

In addition to legal procedures and research techniques, Bazyler taught Stocks about resolve and resiliency, she says. And she isn’t the only one.

“Professor Bazyler has inspired a lot of people who were probably already interested in social justice but now look at these issues in such a meaningful way that it really deepens that connection,” Stocks says.

Across Bazyler’s 30 years of scholarship and research, the rewards are as voluminous as the dusty archives and case files he still scours.

“I tell my students, ‘Look, if you want to go to a big firm and make lots of money, that opportunity is there. I started there. But you can also do pro bono work that can make your career as a lawyer so much more satisfying,’” Bazyler says.

“I want my students to be fighters for justice.”

“Professor Bazyler has inspired a lot of people who were probably already interested in social justice but now look at these issues in such a meaningful way that it really deepens that connection.”