“How am I supposed to make this story my own?” I think this as I watch the video testimony of Holocaust survivor Dr. Sol Messinger. After all, I am not a young Jewish boy. I am not a victim of persecution. I am not a refugee fleeing Nazi slaughter. I am just a student with a writing assignment. So I listen to Sol’s testimony again, closing my eyes and picturing his story.

It is May 13, 1939. I see 937 men, women and children – almost all of them Jewish – boarding the German ocean liner St. Louis in Hamburg, Germany, apprehensive but hopeful that they can escape the hatred of their homelands and find safety in Cuba, where they will wait until they can enter the United States.

During the voyage, the mood is joyful. Captain Gustav Schroeder has ordered his crew to treat the Jews as they would any other passengers. They enjoy good food, music and movies. They relax in the chairs that dot the eight polished decks of the St. Louis. Six-year- old Sol Messinger swims in a pool for the first time in his life; for the first time in a long time, he and the other Jewish children run and play without fear.

On May 27, the ship arrives at Havana Harbor, but it does not dock. “What is going on?” ask worried voices. When the passengers learn that they will not be allowed to disembark, I hear their sobbing. I feel their disbelief. Soon, small fishing boats carrying relatives already living in Cuba encircle the St. Louis. Sol’s favorite cousin, Edith, is with her parents in one of those boats. How happy Sol is to see her! How close she seems as they chat through the porthole in his cabin! But Edith and safety seem very far away when, a few days later, the St. Louis must leave Havana harbor. Despite entreaties from the captain, company officials and the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Cuban president Federico Laredo Bru refuses to allow the passengers into Cuba.

I see young Sol on deck with his father as the St. Louis sails along the Florida coast. His eyes widen when he spots the lights of Miami; they are nearly close enough to touch. His father’s eyes, though, are full of sadness. The passengers’ request for asylum in the United States has been denied. Jewish organizations petition the Canadian government. Denied. They appeal to governments in Central and South America. Denied. Not one of these countries will help.

The television in my family room spits out news of the Syrian crisis, and my eyes open. Images of Syrian refugees mingle with the images I have just been picturing of the St. Louis passengers. And in that instant, Sol Messinger’s story becomes mine to tell.

I have been told that economic and political factors complicate the Syrian situation, just as they complicated the world’s response to the St. Louis passengers in 1939. But while I recognize the complexity, I cannot ignore the complicity of those who choose not to help. As Dr. Messinger explains in his testimony, “The story of the St. Louis really has a statement to make, and that statement is that although the Germans did the actual killing, there were a lot of other countries and a lot of other people who, although they didn’t kill, passively allowed this killing to happen.” In this respect, what we vowed would “Never Again” happen is happening again. How can we sympathize with the passengers of the St. Louis but turn a blind eye to the men, women, and children trying to escape war and persecution today?

I may not yet fully understand all of the concerns that figure into a country’s response to the plight of immigrants and refugees, but I do understand that those concerns must include some consideration for the human beings affected. Soon enough, my classmates and I will be responsible for making decisions that will affect this country and the whole world. I want to be sure that we remember one thing: that the most successful of those decisions will be the ones that reveal an authentic concern for our fellow man.

Lillia Velau is a 10th-grader at JSerra Catholic High School in San Juan Capistrano, Calif. Her essay won first place in the high school division of the annual Holocaust Art and Writing Contest at Chapman University. She wrote about the testimony of survivor Sol Messinger.

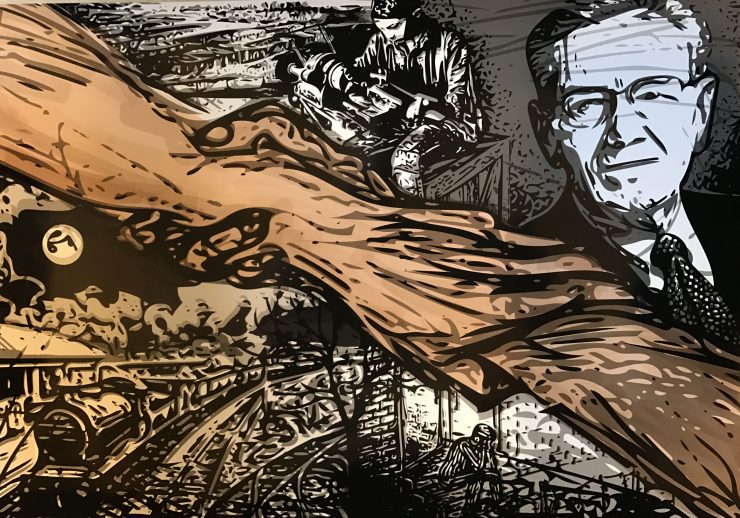

Display image at top/ Hand in Hand, by student artist Rachel Chae

Record Participation for Holocaust Art and Writing Contest

Chapman University’s annual Holocaust Art and Writing Contest reached new heights this year with a record-breaking 250 middle and high schools participating. Now in its 18th year, the contest involves some 7,000 students representing 30 states and eight countries. Each school sent to the final round of judging three entries on the theme “I Have a Story to Tell.”

The award ceremony honoring entries in prose, poetry, art and film was held March 10 in Chapman’s Memorial Hall, with about 1,000 students and teachers and 25 – 30 Holocaust survivors attending.

“This year, at a time when our nation is divided on many issues and when anti-semitism is on the rise, the contest takes on even greater importance and meaning,” said Marilyn Harran, Ph.D., director of Chapman’s Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education, which presents the contest. “Students in the contest come from many backgrounds and represent great diversity, and yet they have all chosen to engage with the story of a Holocaust survivor and learn from it in ways that affirm our shared humanity,” Harran added. “Over the past 17 years, the contest has grown in scope – except in one area: the number of Holocaust survivors in attendance decreases, making the passing on of stories and memories even more vital.”

Art Finalists from the 18th Annual Holocaust Art and Writing Contest:

Add comment