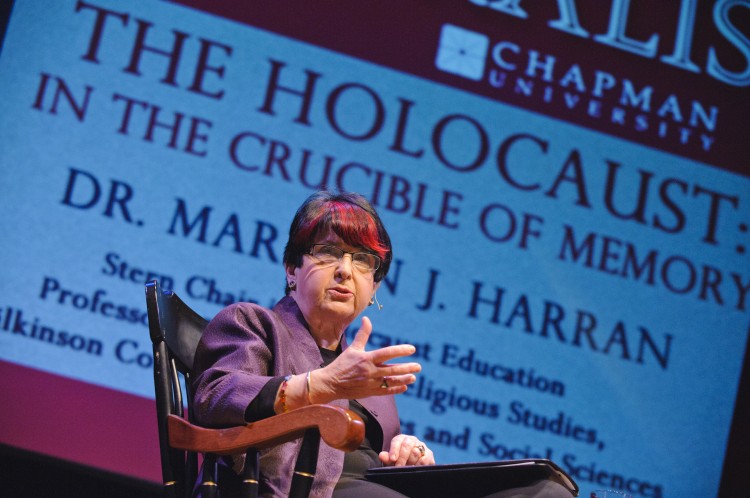

Dr. Marilyn Harran

The Holocaust’s powerful black and white images are memorable, from the photographs of a winsome Anne Frank to the vast files of military photos of the anonymous dead mounded in crematoriums.

But they don’t contain the power of memory.

For that, researchers, students, scholars and anyone wishing to understand the Holocaust – or any catastrophic event of history – much draw closer to the experience, Marilyn J. Harran, Ph.D., told a Memorial Hall crowd Monday night as presenter of Chapman University’s fourth annual

Lectio Magistralis

.

The stories, names, history and memories – especially the memories – of the Holocaust aren’t understood by flipping through photos, but in the act of taking the next step to understanding the experience behind the snapshots, said Dr. Harran, the Stern Chair in Holocaust Education, director of the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education and a professor of religious studies and history.

“We look away, saying we have seen enough, we know enough. Susan Sontag once wrote that the problem is not that people remember through photographs but that they remember only the photos. These photographs become our point of exit rather than our point of entry into the horror of the Holocaust,” Dr. Harran said. “We have seen them so often that we react with Holocaust fatigue.”

In a lecture titled “The Holocaust: In the Crucible of Memory” Dr. Harran incorporated accounts of her oral history research with Holocaust witnesses and survivors, video and – yes – photographs, to illustrate the power of going beyond a textbook study of the Holocaust.

In one example she described a visit to a field where a Nazi death camp once stood. Guiding her was Thomas Blatt, who had been interred at that camp with his family in April, 1943. While his loved ones were sent to the crematoriums, Blatt survived because he was a favored shoe-shine boy. Eventually he joined with other captives in a dramatic escape, found shelter on a nearby farm and was later shot and wounded by the anxious farmer who regretted his decision to harbor Jews.

Upon revisiting the camp site with Dr. Harran he walked to the spot where the crematoriums that had consumed his family once stood, brushed the ground and gathered several fragments of charred, human bone.

“This could be my parents, my brother,” Blatt told Harran. “There were no words I could say. … At that moment the Holocaust became much more to me than the object of historical research and study. It became real. As a teacher I can never replicate for my students the intensity of that experience but I hope that I can guide them, as Tom did me, to find their way into the crucible of memory.”

Linking Holocaust survivors and witnesses with students is one of the cornerstones of

the Holocaust programs

that Dr. Harran heads up. As evidence of what those connections can spark, Dr. Harran closed her lecture with a video interview of dance and music students who created an affecting program of interpretive dance, music and creative readings for last spring’s

Evening of Holocaust Remembrance

.

And in a Q&A following the lecture, Dr. Harran encouraged her listeners to move beyond the routine acknowledgement of the Holocaust with slogans like “Never Again,” even if they could only begin with a few minutes here and there listening to

survivor memories posted online

.

“If we settle for the slogan and we don’t bother ourselves with the pain of coming as close as we can with the history, we don’t really remember anything,” she said.

Chapman Newsroom

Main Menu >

Media Contacts

Office of Public Relations

PR@chapman.edu

Strategic Marketing and Communications

1 University Drive

Orange, CA 92866

Contact Us

Strategic Marketing and Communications

1 University Drive

Orange, CA 92866

Contact Us

Newsroom Site

Your Header Sidebar area is currently empty. Hurry up and add some widgets.

hi

wierd